Building a reliable asynchronous job pipeline

Asynchronous background jobs can dramatically improve the performance and scalability of web applications by offloading resource-intensive and time consuming processing from the request-response cycle of an application.

Last year, in an effort to make our asynchronous flows more reliable, secure, and scalable, we decided to move away from our self-hosted solution that was based on RabbitMQ and Kafka, to a fully-managed one. This was done mainly to reduce the operational overheads in managing and scaling the underlying infrastructure and also to improve our overall security posture.

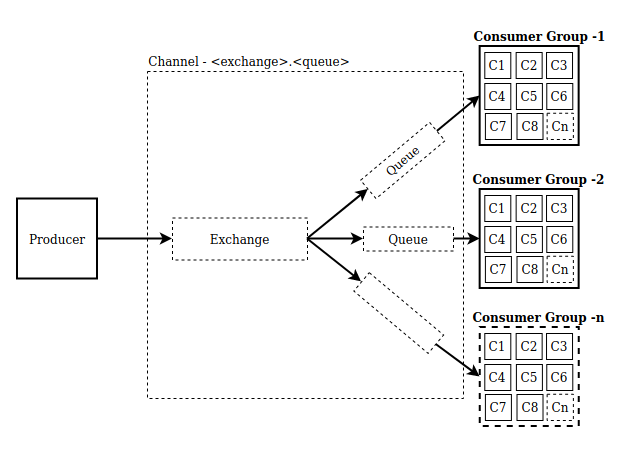

To support this flow, we created a new library called he-messenger that implements an end-to-end queuing solution for allowing different services or different components of the same service to communicate with each other asynchronously. This library is built on top of the SQS, SNS, and S3 - managed services provided by AWS. It is a fully serverless solution that ingests events from different services, buffers them, and then delivers those events to the subscribed services in a reliable way. It simplifies the otherwise laborious process of provisioning and scaling self-hosted infrastructure.

Since its introduction, this library has become one of the critical pieces of our architecture powering a lot of different use-cases with a very high number of transactions

There are many open-source libraries available in the market that use AWS managed services to support asynchronous background jobs. However, none of them offered an end-to-end solution and the kind of guarantees we needed. Therefore, we decided to implement our own custom library to support this flow.

The purpose of this blog is to give you an overview of the internal and the code level details of the he-messenger library along with a sample reference architecture, supported flows, features,and benefits of this solution.

Terminology

- Channel: An abstract communication layer responsible for passing messages between producers and consumers. A channel abstracts out all the underlying implementation details around the SNS, SQS and S3 services that we use for different purposes internally. The name of a channel can be either of the following based on the type of consumer:

- Single consumer case

- In this case, the channel consists of an SQS queue only.

- Format:

<queue_name>

- Multi-consumer case

- In this case, the channel consists of both the SNS topic and the SQS queue subscribed to that topic.

- Format:

<exchange_name>.<queue_name>

- Single consumer case

- Producer: Implements the functionality required to push a message to a channel

- Consumer: Implements the functionality required to listen, consume, and process a message that was pushed to a channel

Key concepts

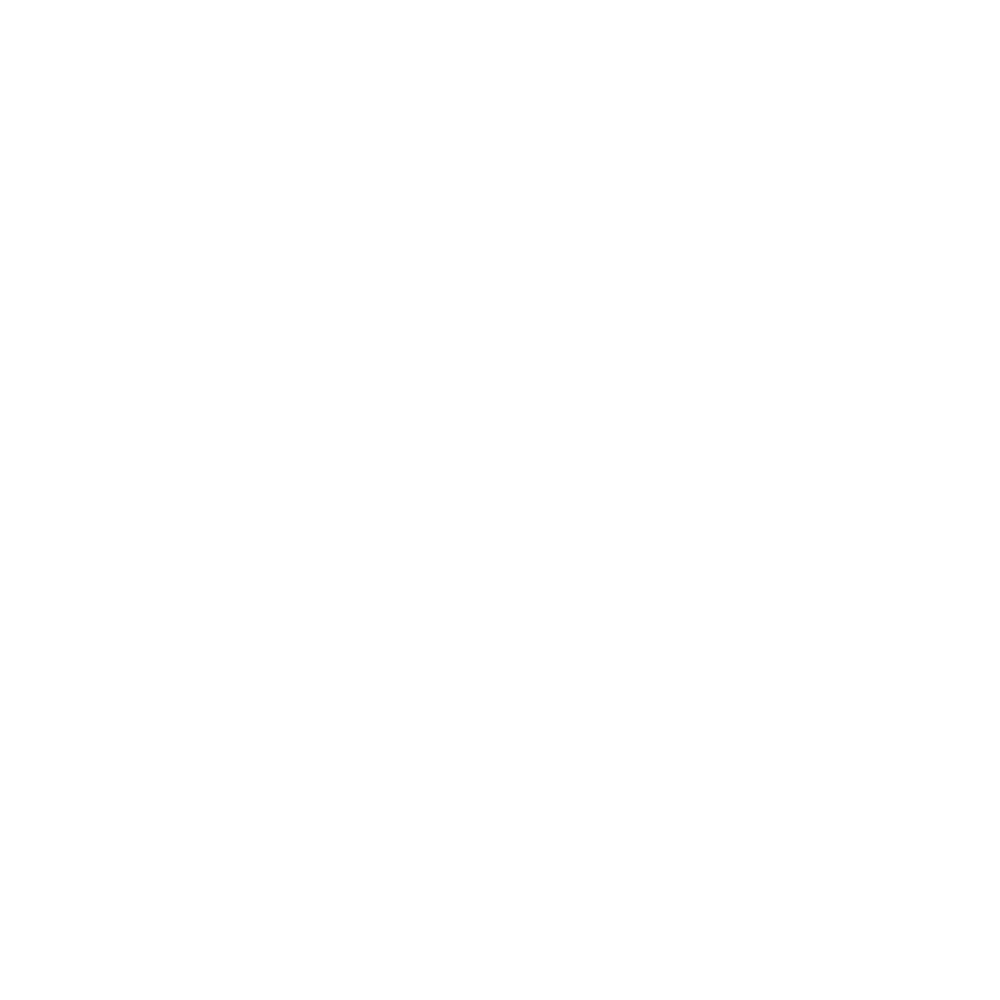

1. One-to-one flow

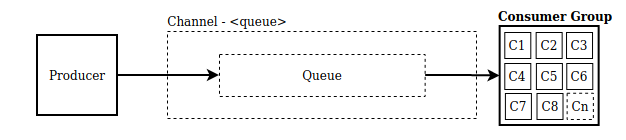

2. One-to-many flow

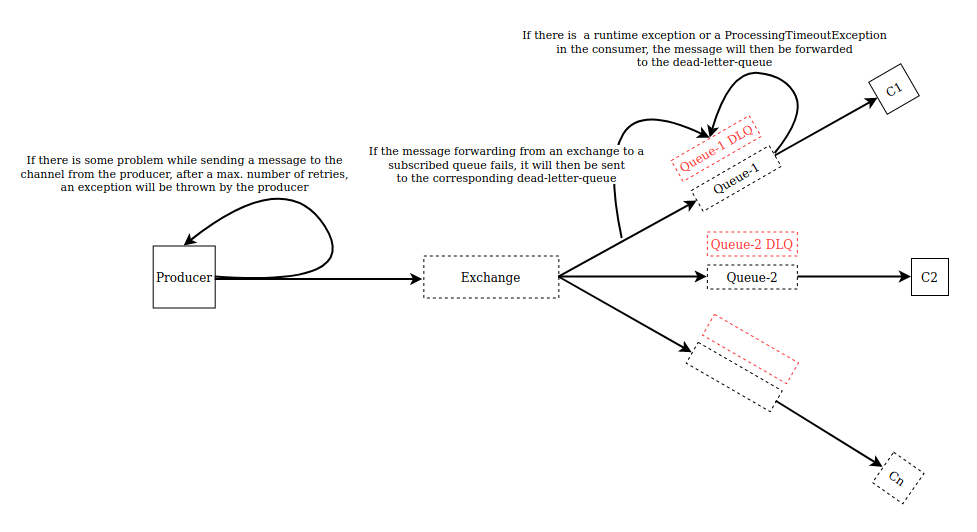

The main difference between one-to-one and one-to-many flows is the type of the resource to which the producer pushes a message. In the one-to-one flow, the producer pushes a message directly to an SQS queue, whereas, in the one-to-many flow, the message is first pushed to an SNS topic and from there it is broadcasted to all the subscribed SQS queues.

Infrastructure

Implementation

Producer

A producer implements the functionality required to push a message to a channel. Producer instances are implemented as thread-safe singleton objects. During the initialization, we ensure that all the infrastructure dependencies of the channel are fulfilled before we start using it for the message delivery. This will remove the overhead of checking the infrastructure dependencies every time the message is pushed.

Producers don’t really know anything about the subscribers/consumers of its message channel. In a way, they are totally decoupled. Producers will always push a message to a single channel. Consumer groups will then subscribe to that channel without knowing anything about the producers. This will allow us to have the producer class defined in one microservice and the corresponding consumer classes in a totally different set of microservices.

Ideally, all producers should push their messages to the SNS topics and the consumers should be solely responsible to create the SQS queues and to subscribe to the SNS topics that they are interested in. Like a proper publish-subscribe model.

However, due to cost concerns, we decided to go ahead with an approach where we will push messages to either an SNS topic or an SQS queue depending on the subscriber type that we configure when we define the producer.

While pushing a message, if an infrastructure provisioning error occurs, the producer will try to reprovision all the required resources in an idempotent manner. And if some transient infrastructure exception occurs, for example API throttling, then the producer will retry that operation with an exponential backoff for a maximum duration of 15-20 seconds. In cases where there are any other runtime errors, the exception will be thrown explicitly.

Message ordering is another important capability that the producer supports. If it is enabled, the order in which messages are sent and received is strictly preserved and each message is delivered exactly once. Moreover, any message that is published with the same content to an ordered channel within a five-minute interval will be rejected by the system (message deduplication). This will enable enhanced messaging between applications where the order of messages is critical or where duplicate messages cannot be tolerated. End-to-end message ordering is supported in both one-to-one and one-to-many flows.

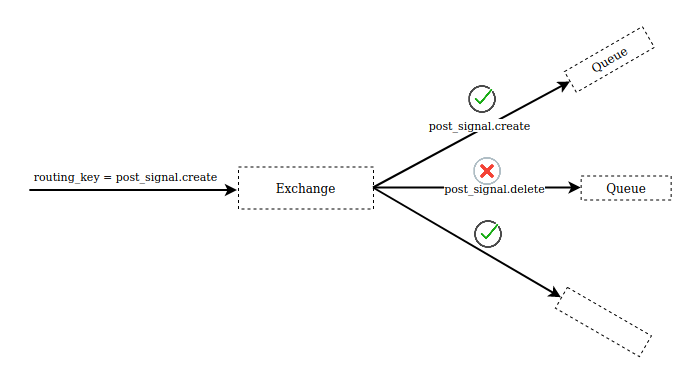

In a one-to-many scenario, a special key called a routing_key can be passed along with each message that a producer produces. The consumer groups can choose to listen to only a subset of the incoming messages depending on the routing key value of the message. Supported filter types on the consumer side are:

- Exact match filter

- Prefix match filter

- Exclude filter(with exact match)

# Producer class

class WishListEventProducer(MultiProducer):

channel = 'wishlist_events_exchange'

ordered = True

WishListEventProducer().push(body=..., routing_key='MOBILE.APPLE')

WishListEventProducer().push(body=..., routing_key='LAPTOP.LENOVO')

WishListEventProducer().push(body=..., routing_key='MOBILE.ONEPLUS')

# Consumer classes

# Receives all messages

class AuditWishlistEventsConsumer(Consumer):

channel = 'wishlist_events_exchange.audit_log'

ordered = True

delay = 10 # 10 sec delay

# Receives only those messages with 'MOBILE.' prefix in their routing keys.

class ProcessMobileEventsConsumer(Consumer):

channel = 'wishlist_events_exchange.process_mobile_events'

ordered = True

delay = 30 # 30 sec delay

message_filter = MessageFilter(filter_type='prefix', values=['MOBILE.'])

# Receives only those messages with 'MOBILE.APPLE' as the routing key.

class ProcessAppleMobilesConsumer(Consumer):

channel = 'wishlist_events_exchange.process_apple_mobile_events'

ordered = True

message_filter = MessageFilter(filter_type='exact', values=['MOBILE.APPLE'])

Consumer

A consumer implements the functionality required to listen, consume, and process a message that was pushed to a channel. It will always be listening to an SQS queue and will be the owner of that queue, thus responsible for provisioning and maintaining the underlying queue infra.

We wanted our consumer implementation to be simple and reliable. Inside the container environments where we usually run our consumers in, we wanted to make sure that we are running only the main entry point process and nothing else apart from it. We did not want to spawn additional processes/threads to monitor the health of the consumer or to send heartbeat messages to keep the consumer connection alive, like in our previous implementation(RabbitMQ-based). Because that would introduce an overhead in monitoring those additional processes and in making sure that all those processes are up and running all the time alongside the main container process (PID 1). The reliability of the container entry point process is taken care of by the AWS ECS system that we are using for container orchestration and management.

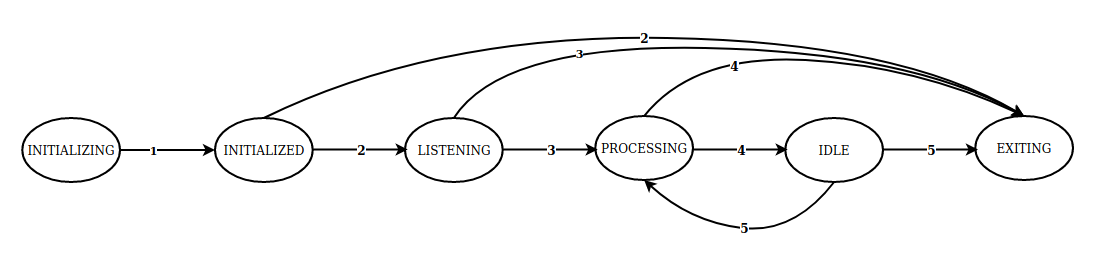

The consumer is implemented as a state machine. This helps us in configuring lifecycle hooks and triggering event handlers on state transitions. This pattern gives a lot of flexibility to the developers in implementing custom wrappers around the message-processing part and custom handlers that get triggered at different stages of the consumer lifecycle. Moreover, this allows us to have a different set of event handlers for different consumers unlike in our previous implementation where we could only have a single common wrapper for all the consumers. Furthermore, this pattern significantly improves the code readability by placing the event handlers alongside the main consumer logic.

On the consumer side, if a message processing is taking a lot of time, then the overall throughput of that consumer pool may drop. This could lead to longer wait times in the queue that will in turn have an effect on the average processing latencies of that flow. What if there are a lot of such rogue messages being processed by the consumer pool almost during the same time? What if the processing time of a specific message is directly proportional to the length of the inputs and some of them are taking forever to get processed? How to handle such rogue or long-running messages without affecting the overall throughput of the consumer pool? Yes, what you guessed is right. We somehow need to put a cap on the processing time of a single message depending on the use case of the given consumer. That’s exactly why we introduced a new parameter called processing timeout in our consumer config. This parameter was introduced mainly to limit the processing time of a particular message.

Processing timeout is the maximum time taken by the consumer to process any given message. The developer has to set this to a sensible value so that this threshold is never reached in normal scenarios. This number can eventually be tuned to a much more accurate limit with the help of APM tools like NewRelic or DataDog, based on the historical performance of that consumer. If the processing timeout threshold is reached before the message processing is complete, then the consumer will abruptly stop processing the message, raise the ProcessingTimeoutException exception and it will then start processing the next available message in the queue. The failed message will then be forwarded to the corresponding dead letter queue (exception queue), if configured. Otherwise, the exception will be raised explicitly and the consumer process will be terminated.

We allow developers to set the value of the processing timeout to any integer between 1 second and 1800 seconds (30 minutes) depending on the use case. Here is the sample implementation:

import signal

def register_signal(self, _signal, _handler):

signal.signal(_signal, _handler)

# Make sure that the system calls are restarted when

# interrupted by the given signal.

signal.siginterrupt(_signal, False)

def timeout_handler(self, _signal, _frame):

raise ProcessingTimeoutException

@contextmanager

def ticker(self, timeout):

register_signal(signal.SIGALRM, timeout_handler)

signal.alarm(timeout) # Setting SIGALRM timeout to `timeout` seconds

try:

yield

finally:

if self.should_reset_timeout_alarm:

signal.alarm(0) # Resetting SIGALRM timeout to 0

with ticker(processing_timeout):

handler(message) # Process the message

Delay tolerance is another new parameter that we added to our consumer config. It is the maximum allowed delay in processing a message from the point from when it was pushed to the corresponding channel. The developers need to set this value to a sensible number depending on the processing time of the message along with sufficient buffers. In our case, the default value is 2 minutes. If this option is configured, the system will try to process the message within the tolerated delay on a best-effort basis. As of now, this parameter is not being used actively in any of our flows but the plan is to use it to adjust the capacity of the consumer pool dynamically to make the time taken for message processing fall within the delay-tolerance limits of the given consumer.

The SQS moves messages from the source queue to its corresponding dead-letter-queue if the consumer of the source queue fails to process a message for a specified number of times. In our case, we retry it for a maximum of three times.

def handle_processing_timeout_error(message, err):

# Trigger `ON_PROCESSING_TIMEOUT` life-cycle hook

trigger_hook(ConsumerHooks.ON_PROCESSING_TIMEOUT, message)

if dlq:

# Forward the message to the corresponding dead letter queue

forward_message_to_dlq(message)

else:

# Re-raise the exception if no dlq is configured.

raise err

def consume():

# Transition the consumer to the `LISTENING` state

transition_to_listening_state()

# Continue to listen to the queue for new messages until a graceful shutdown signal is received

while not signal_received:

should_reprocess_message = False

# Receive a message from the queue if available. Otherwise wait for a max. of 20 seconds before we conclude that there are no messages available.

message = receive_message()

if not message:

continue

try:

# Transition the consumer to the `ConsumerStates.PROCESSING` state

transition_to_processing_state(message)

# Start a ticker to make sure that the processing of the message

# would not exceed the `ProcessingTimeout` seconds.

with ticker(processing_timeout):

# Process the message

handler(message)

except ProcessingTimeoutException as err:

handle_processing_timeout_error(message, err) # Consumer took too long to process the message

except Exception as err:

handle_runtime_error(message, err) # Runtime error while processing the message

finally:

if should_reprocess_message:

# Redelivers the message to the same queue with a 5 second delay.

message.redeliver(delay=5)

else:

# Deletes the message from the queue.

message.delete()

# Transition the consumer to the `ConsumerStates.IDLE` state

transition_to_idle_state()

Consumer states

Custom wrappers

The processing of each message can be wrapped within a custom functionality as shown below.

Example: Internationalization

To make all our asynchronous background jobs internationalization (i18n) aware, we pass the locale context along with the main message payload.

# On the producer side

class MyProducer(Producer):

# Mainly to pass some extra context alongside the message payload

def meta_headers(self):

meta_headers = super(Producer, self).meta_headers()

meta_headers.update({

'locale': get_current_locale()

})

return meta_headers

The locale context associated with each message can be used to make the message processing part i18n aware on the consumer’s end.

# On the consumer side

class MyConsumer(Consumer):

@register_hook(LifecycleHooks.MSG_PROCESSING_START)

def message_processing_start_handler(self, message):

locale = message.meta_headers['locale']

activate_locale(locale)

@register_hook(LifecycleHooks.MSG_PROCESSING_END)

def message_processing_end_handler(self):

deactivate_locale()

# Those handlers will be executed in the following order:

1. Receives a message from the SQS queue

2. Calls MSG_PROCESSING_START handler

3. Calls the main message handler

4. Calls MSG_PROCESSING_END handler

Consumer instrumentation

Instrumentation of the message handler can be done by slightly modifying the consumer-handler logic. The following example shows a way to integrate the NewRelic APM client with the consumer class for instrumenting the message-handler logic.

class MyConsumer(Consumer):

channel = "update_phonenumber"

def handler(self, message):

if os.getenv("APM_INSTRUMENTATION_ENABLED"):

import newrelic.agent

with newrelic.agent.BackgroundTask(newrelic.agent.application(),

name=self.channel):

super(Consumer, self).handler(message)

else:

super(Consumer, self).handler(message)

Consumer health checks

We periodically monitor the health of our consumer containers to ensure that they are actively listening to the queue, consuming messages, and processing them within the expected timeframe.

If a consumer is stuck at any of the states — INITIALIZING, INITIALIZED, PROCESSING, or EXITING — due to some reason, we try to kill that container gracefully and spawn a new one to replace it. Health checks are configured using Docker HEALTHCHECK command.

Here is the health check configuration from one of our consumer task definitions:

"healthCheck": {

"command": [

"CMD-SHELL", "check_consumer_health || exit 0"

],

"interval": 30,

"timeout": 10,

"retries": 5,

"startPeriod": 300

}

In this we use a file to do inter-process communication between the main consumer process and the health check process. Whenever the consumer process transitions from one state to another, it writes the required data to a file. The health check process periodically reads and processes that data to determine the current state of the consumer process. We lock that file while reading from or writing to it to ensure data correctness.

Here is the sample implementation of the script that is responsible for performing consumer health checks:

# check_consumer_health.py

import datetime, json, os, sys

from filelock import FileLock, Timeout

CONSUMER_STATES_TO_MONITOR = ['INITIALIZING', 'INITIALIZED', 'PROCESSING', 'EXITING']

def process_health_check_data(data):

state = data['state']

healthcheck_timeout = data['healthcheck_timeout']

state_transition_timestamp = data['transition_timestamp']

state_transition_datetime = datetime.datetime.strptime(

state_transition_timestamp, '%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S.%f')

now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

time_elapsed = (now - state_transition_datetime).total_seconds()

if int(state) in CONSUMER_STATES_TO_MONITOR and time_elapsed > healthcheck_timeout:

return False

return True

def check_consumer_status():

try:

# Wait for a maximum of 5 seconds for acquiring the lock

with FileLock('/tmp/health_check_file.lock', timeout=5):

contents = None

with open('/tmp/health_check_file', 'r') as f:

contents = json.loads(f.read())

status = process_health_check_data(contents)

if status is True:

sys.exit(0)

else:

sys.exit(1)

except IOError:

sys.exit(0)

except Timeout:

sys.exit(0)

except SystemExit:

raise

except:

sys.exit(1)

if __name__ == "__main__":

check_consumer_status()

Graceful consumer shutdown

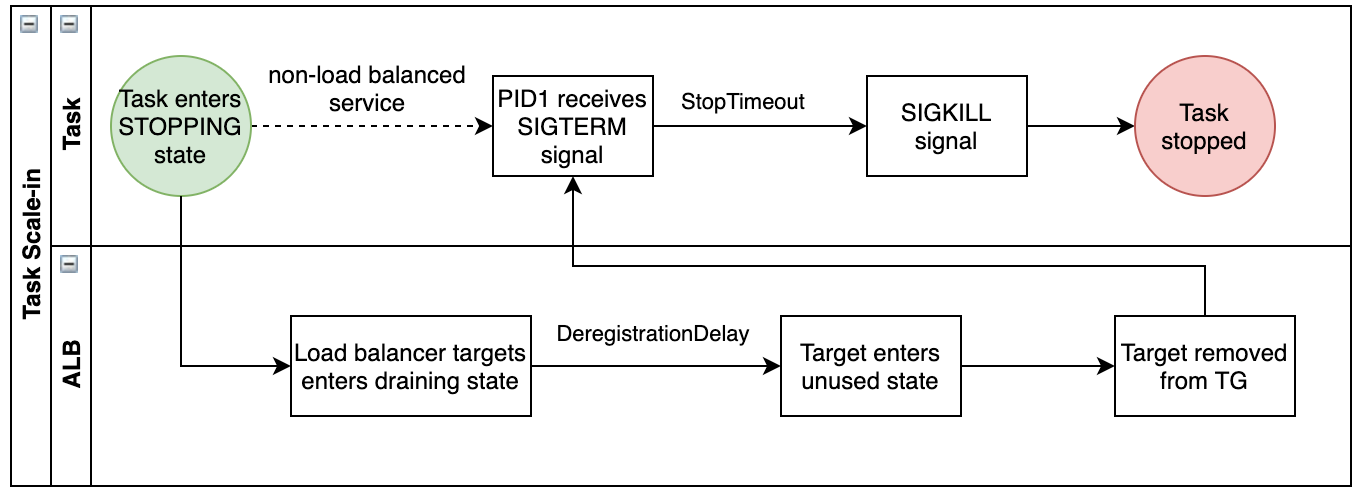

Shutting down consumer processes gracefully is important to prevent partial processing, data loss, bad exits, or unreleased resources. While terminating a container, the ECS system will first send a SIGTERM signal to the container’s entry-point process (usually PID 1) to notify it that it will be killed. Once the consumer process gets this signal, it will stop consuming new messages from the queue, finish the ongoing processing if any and clean up the resources it used.

When a SIGINT or SIGTERM signal is received by the consumer, it will wait for a maximum of 30 seconds before it kills itself in an abrupt way. This will ensure that the consumer process gets sufficient time to finish the pending processing and make a clean exit. The following diagram explains the container shutdown flow of an ECS task.

(Source: AWS Documentation)

(Source: AWS Documentation)

Handling large messages

If the total message payload size (including body and attributes) crosses the 256KB threshold, then:

- The contents of the message will be offloaded to the S3 storage

- The S3 object reference will be sent as part of the main SNS/SQS message payload

he-messenger abstracts out the complexity around handling large messages and exposes only the fixed contracts for pushing and receiving messages irrespective of the size of the message.

Message retention

If due to some reason, the messages that are getting pushed to a channel from the producer’s end are not getting consumed on the other end, then it may result in the accumulation of messages inside the channel’s buffer (either in SQS or S3). Such messages will continue to be available for consumption till the maximum message retention period of 14 days is reached. The system will automatically delete or expire the messages that exceed the retention period. Longer message retention provides greater flexibility for developers to debug, fix, and requeue any problematic messages from DLQs to their corresponding source queues easily.

Content encryption

Encryption at rest (server-side encryption) and encryption in transit have been enabled in all three underlying AWS services—SNS, SQS, and S3. Messages stored in both the standard and the ordered channels are encrypted using a customer-managed, KMS encryption key.

Message requeuing

We have implemented a requeuer utility that helps us in consuming messages from a queue, for example, a dead-letter queue, and pushing them to the destination channel.

This is how we trigger message requeuing from one channel to another:

requeuer = Requeuer(

source_queue='<source queue name>',

destination_channel='<destination channel name>',

destination_type=SubscriberTypes.MultiConsumer

)

requeuer.start()

Local development

In this mode, the producers and consumers will try to connect to the Localstack server, which is a mocking framework for AWS services, running locally instead of talking to the actual AWS services. This allows us to develop and test the asynchronous flows in our local machine without ever talking to the AWS cloud. Activation of this mode is handled by environment-specific variables. To achieve this without a lot of code-level changes, we monkey patch the entry points of the boto3 package with localstack specific ones.

Here is the sample implementation code:

def patch_boto3():

import localstack_client.session

localstack_session = localstack_client.session.Session()

boto3.client = localstack_session.client

boto3.resource = localstack_session.resource

if LOCAL_ENVIRONMENT:

patch_boto3()

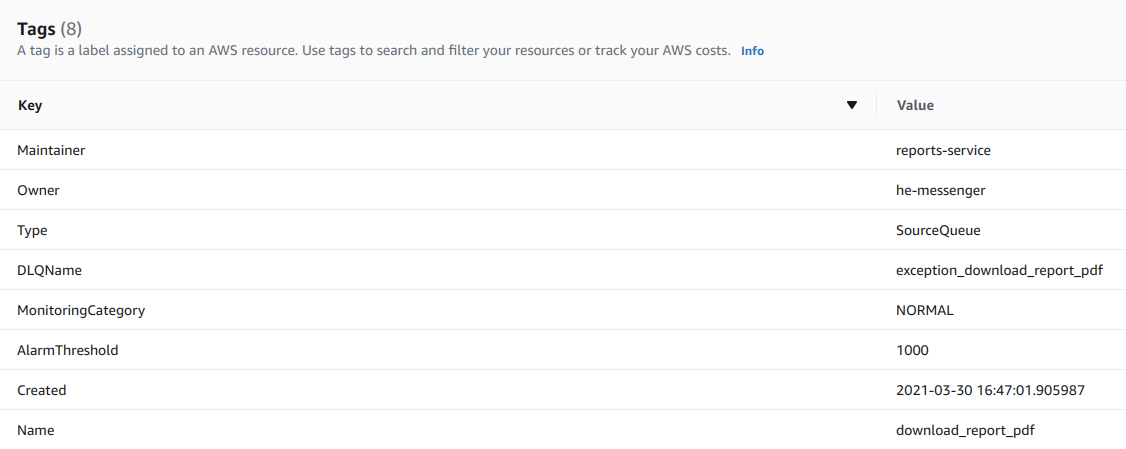

Infrastructure ownership and tracking

he-messenger owns all the infrastructure that it provides as part of our asynchronous flows. It takes the responsibility of provisioning, maintaining, and cleaning of those resources. We use AWS resource-level tags to store ownership information, alarm thresholds, and other related meta information. Tags help us have a detailed breakup of the AWS costs per resource or per use-case. Here is a sample list of tags that we usually store along with each resource that is provisioned through he-messenger.

Error handling

We made sure that the transient errors are handled gracefully by configuring retries at the interfaces between any 2 components, for example, producer-SNS interface, SNS-SQS interface, etc. Messages that cannot be delivered by an SNS topic to its subscriber queues due to client errors or server errors are eventually routed to the corresponding dead-letter queue for further analysis or reprocessing.

If there is a ProcessingTimeout exception or any other runtime exception, the message will eventually be routed to the dead-letter queue. Therefore, a message that is published from a producer to the channel will always be available either in the source queue or the dead-letter queue if it has not been deleted by the consumer.

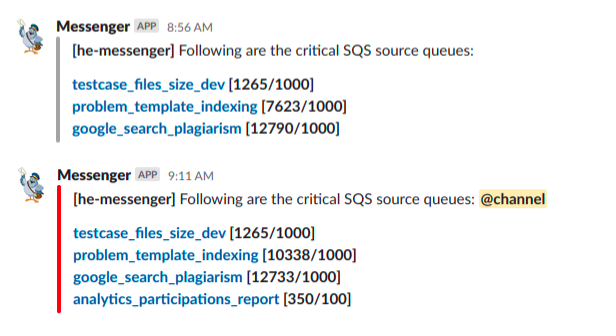

Alerting

he-messenger auto-configures alerts for all the SQS queues that it owns to send notifications about the problematic queues if any. It runs two lambda functions periodically to monitor both the source queues and the dead-letter queues every 15 minutes and 12 hours respectively.

A lambda function checks the value of the ApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisible metric for each of the queues and also checks if that value is crossing the configured alarm threshold. It also checks whether any of those problematic queues are tagged as critical. It will flag these during notifications.

Here are the two different message variants (non-critical and critical) that he-messenger posts to our internal Slack channels if there are any problematic queues:

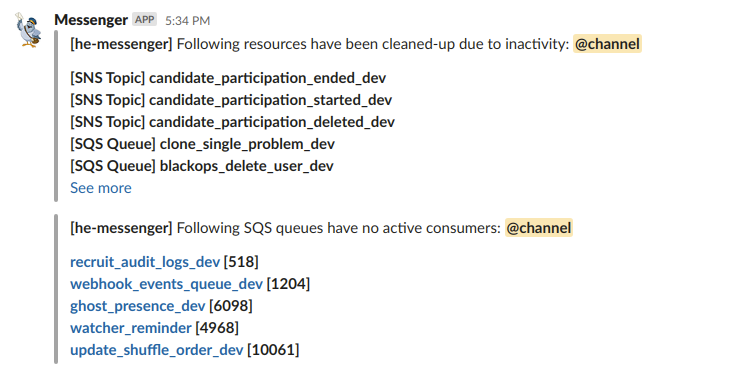

Resource cleaner

All unused or inactive AWS resources provisioned by the he-messenger service will eventually be deleted by the resource-cleaner utility, which is an AWS lambda function that runs once every day.

Here are the steps that are used to classify and clean up unused resources:

- Get all SNS topics and SQS queues owned by the he-messenger service.

- Filter the SNS topics that have zero metric value consistently for the past 1 day for the following metrics:

- NumberOfMessagesPublished

- NumberOfNotificationsDelivered

- Mark those SNS topics as inactive

- Get a list of active SNS topics by removing the inactive topics from the list of valid SNS topics owned by he-messenger

- Mark all those SQS queues that are subscribed to these topics as active.

- Get the values of the following metrics for each of the valid queues for a 3-day duration:

- ApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisible

- NumberOfMessagesSent

- NumberOfMessagesReceived

- NumberOfEmptyReceives

The sum of the values of NumberOfMessagesReceived and NumberOfEmptyReceives metrics represent the behavior of the consumer pool listening to the given SQS queue. If the sum is zero, that basically means there are no consumers listening to this queue actively.

- Classify the queues into the following categories based on the values of the metrics mentioned above:

- Inactive queues with no messages (to be deleted)

- Inactive queues with stale messages (to be notified)

- Queues with no producers (to be notified)

- Queues with no consumers (to be notified)

- If the values of NumberOfMessagesSent and (NumberOfMessagesReceived + NumberOfEmptyReceives) metrics are consistently zero, the queue can very well be marked as inactive if it is not subscribing to any of the active SNS topics.

- If the value of the ApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisible metric is zero for any of those inactive queues then they will be marked for deletion. Otherwise, they will be categorized as ‘Inactive queues with stale messages’.

- In the remaining queues, if the value of the NumberOfMessagesSent metric is consistently 0, those will be categorized as ‘Queues with no producers’.

- In the remaining queues, if the value of (NumberOfMessagesReceived + NumberOfEmptyReceives) metric is consistently 0, those will be categorized as ‘Queues with no consumers’.

- The infra cleaner reports the following metrics to the Engineering team:

- Unused SNS topics deleted

- Unused SQS queues deleted

- SQS queues with stale messages

- SQS queues without active producers

- SQS queues without active consumers

Here are the sample messages that he-messenger sends after cleaning up unused resources.

Conclusion

We built he-messenger to reliably and effectively run resource-intensive or time-intensive tasks asynchronously in the background. We were able to migrate all our existing flows to this new flow pretty smoothly without any hiccups. It is now responsible for running hundreds of asynchronous flows while catering to some of the most critical use cases at HackerEarth for the past one year. We are planning to make this library open source soon. If you are interested in working on projects like this and helping recruiters find the right talent they need, HackerEarth is hiring!

If you have any queries or wish to talk more about this architecture or any of the technologies involved, you can mail me at jagannadh@hackerearth.com.

Posted by Jagannadh Vangala